One

When the medical personnel in the ICU pulled the plug on my father, it was anticlimactic for me. I can’t speak for my two sisters who were there, nor for my brother who was (as I recall) not there but was somewhere near the hospital in Kalamazoo, or perhaps somewhere back in Dowagiac. To be candid, I don’t reliably remember which of my siblings were there.

What I clearly recall is that when the time came, we all seemed to adopt a similar poise and decorum. We each took a turn to sit by his side and briefly say something in his ear, not knowing whether any of his mind was left for him to hear and understand it, but before and after that each of us stood outside the room and yielded the space around our father to his third wife, to her son who he’d come to regard as his own, and to the many adopted grandchildren and great-grandchildren who had been born and were being raised with him as their beloved patriarch.

I felt no envy or resentment toward my father or my step-brother. I felt a sympathetic sadness for my step-brother, who I shall call ‘Mike,’ and for his children as they all crowded around my father’s dying body and wept and wailed and begged him not to go. I understood, perhaps instinctively in that moment, and certainly consciously in retrospect, that Mike and his children and grandchildren were in the process of being torn away from a love and a paternal presence that I had already lost before I was old enough to comprehend.

I must disclose here that two of my brothers did spend time living with my father, from their early high school years until they became independent. It’s fair and accurate to say that those two established relationships with him that became similar in depth to that of my step-brother. So while it’s possible and likely that some of our other siblings share a version of the alienation that I illustrate above, I can only justly attribute it to me. I’d gotten to know my father a bit better since the birth of my daughter, and I enjoyed the times we spent together. I’m glad my daughter got to know him. So when I say that my father was, in a sense, already dead to me by the time he breathed his last breath, it is not to express the bitterness that such words usually intend. It’s merely to illustrate that I had no basis for the sense of loss that some of my brothers felt.

I can only imagine the emotional dilemma of my older half-brother (we’ll call him ‘Kevin’ here), who is one of two children my father had with his first wife, before marrying my mother. While my father’s various children and surviving siblings and other relations and acquaintances gathered in a church in Dowagiac to mourn and reminisce, Kevin sat in a car in the parking lot. I’d known Kevin since I was a toddler – he would visit with us occasionally, even long after our father had moved on to Wife #3 – but during and after the funeral it never occurred to me to ask him how he felt about having lost his dad several times, in several ways, and now finally. His inability to leave the church parking lot said enough, I suppose.

Two

I grew up in a small raised ranch house on the South Side. The house now sits unoccupied, dormant except for what is probably a hazardous level of mold growth. I’ve received several calls from individuals interested in buying the property, and I’ve truthfully told them that I have no attachment to it, neither legal nor emotional. As far as I know, not one of my siblings who were raised in that house has any such interest in it, with the possible exception of my two sisters perhaps wanting to retrieve what they can of our mother’s extensive photo collection.

The house remains in my mother’s name, though she will never again set foot in it. She suffers from a form of dementia that will keep her institutionalized for the rest of her life. I visit her occasionally, picking her up from the nursing home to take her out to lunch and maybe to go shopping for a paperback romance novel or a new coat or pair of shoes.

In the couple of hours I’m with my mother, I do my best to keep our conversations light and trivial. I’m not qualified to diagnose her current condition, and I’m certainly not equipped to wade into the unknown childhood traumas that must have helped to make her into such a dutiful, stern, distant, paranoid, and occasionally vicious parent. It helps that her short-term memory seems to hold no more than about fifteen minutes on a good day; the old grudges are easy to avoid while she’s incapable of forming new ones.

It’s best to stop this portion of our discussion right here. There is a world of things about my mother that I don’t wish to share, and to do so would be unfair to my siblings who’ve likely experienced their own versions of what I could only attempt to describe.

Three

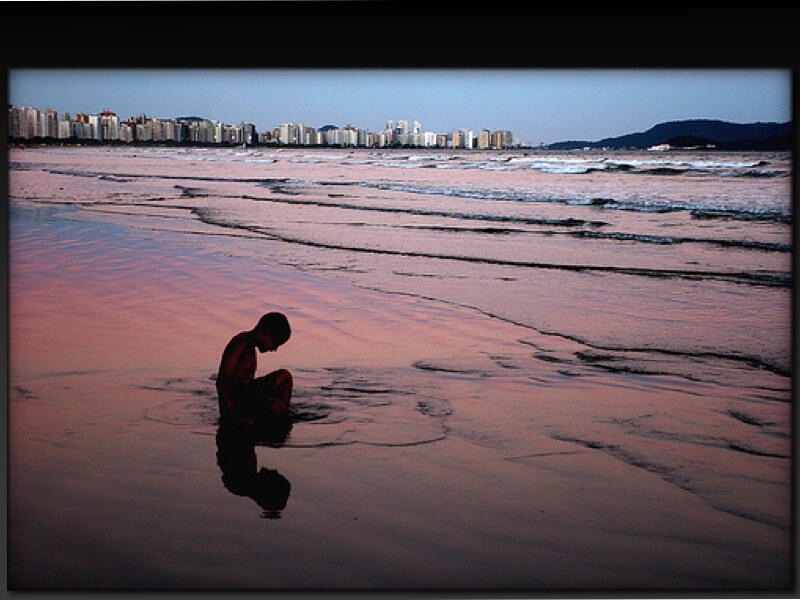

I think my family’s decaying former home is to me what our father’s funeral service might have been to Kevin. It is a place I am all but physically barred from entering. It is a physical representation of my alienation from that which should have been a haven of unconditional affection and fealty.

I think of this alienation as a void or vacuum that has displaced childhood memories and familial attachments. I may sense its boundaries when I’m with my siblings or when I think of them, or when my daughter asks me questions about my youth that I am usually unable to answer in detail, but it causes me no distress. That which never existed, need not be mourned.

I wish I could say that there’s some profound meaning to what I’ve shared, but I can see none. I believe alienation is endemic to human experience within the context of what we know as civilization, and that every one of us lives with a manifestation of it. I’ve shown you a fragment of my own, and I don’t even claim that it qualifies as traumatic.

So maybe this is, obliquely at least, a cautionary tale. If so many of us among the billions are able to function while being so alienated from one another – and much more so from the natural world that sustains us – then what incentive will we have to form more sustainable bonds? I can’t even answer for myself.

IN THIS ISSUE

- BIG MOODY MOUNTAIN, by Tia Creighton

- MARK OF THE HEALER, by Sam Holloway

- ADVICE FROM THE WORLD’S SECOND GREATEST NETFLIX PITCHER, by Jonathan

- HERRINGBONE! HERRINGBONE!, by The Editors

- APOCALYPSE STORYTIME, by Tia Creighton

- SO FAR, WE REGRET HAVING YOU, by Tia Creighton

- INCREMENTAL REPORTS, by The Editors

- TOP OF THE HEAP, by Tia Creighton