“Your own history tells you. Your people are intelligent, and that’s good…But you’re also hierarchical…You’re bright enough to learn to live in your new world, but you’re so hierarchical you’ll destroy yourselves trying to dominate it and each other.”

Octavia Butler, Adulthood Rites, pp. 264-265

In its June 27, 1948 issue, The New Yorker Magazine included what was arguably one of its most controversial short stories to date and since. Shirley Jackson’s “The Lottery” generated an avalanche of immediate feedback for the magazine, most of it negative (1). Hundreds of readers were horrified and confused enough to cancel their subscriptions. Jackson began receiving a steady stream of hate mail, and even her parents openly expressed dismay at the story.

“The Lottery,” for the uninitiated, depicts a small, contemporary New England village as it conducts its annual lottery to determine which villager will be stoned to death. While much has likely been written about Jackson’s possible motivations for writing the story, this analysis will be informed more by the reactions. Most 1948 readers of The New Yorker had to have been aware, as doubtless was Jackson, of the horrors of the Nazi-led Final Solution in Europe just a few years before, and of the mass slaughter of Allied carpet-bombings on German and Japanese cities that had culminated in the deployment of an unprecedented and potentially apocalyptic weapon of war. Why, then, did the situation of ritual human sacrifice in a mundane, modern, and culturally familiar setting discomfit so many presumably sophisticated readers? It is beneath that jarring cognitive dissonance that we must look, if only to find whether ritual human sacrifice is either as obsolete or as incongruous to our modern, liberal societies as we might wish to believe.

In his analysis of violence in ritual, Tom F. Driver states that its roots “lie not in religion as such but in the very human desire to display control over life and death by means of ritual” (2). We tend to characterize ritual human sacrifice as archaic, something we have through evolution of custom and law moved beyond. If this is true, then how far into antiquity does Driver’s principle apply? Is there a roughly definable point at which we can say that ritual human sacrifice became taboo?

Before we attempt such quantification, we must further articulate our definition of ritual human sacrifice within the parameters set forth by Driver. He begins his analysis with this explanation:

…all ritual, understood as a species of performance or live enactment, harbors an inclination toward violence. Murderous violence becomes sacralized by ritual enactment. Conversely stated, the sacralizing function of ritual includes a tendency to sacralize the murder of humans and the slaughter of animals. Sacralized violence is justified by the name “sacrifice” (3).

Driver posits that the violence inherent to such ritual exists before the concepts used to justify it, and that this violence is “something more elemental than theology or myth or social structure”(4), namely, in part at least, the desired control over life and death. If, however, we can rationally accept that such control is impossible for us, and was likely considered so for our ancestors, then it follows that there are other additional motivations.

One possible factor is evolutionary. Paul M. Bingham argues “that all major elements of human uniqueness follow directly from our unprecedented levels of nonkin cooperation” (5). Simply put, nonhuman animals tend to organize around closely related groups. Human development has allowed for and been driven by the ability for cooperation between humans who are not closely related. This has led to a collection of sophisticated interactive behaviors and concepts not simultaneously present in nonhuman animals, including language differentiation and punishment. Thus, human society has forever endured an often tense balance between group cohesion and individual interest. Perhaps it is this tension that eventually situated interpersonal violence within ritualization.

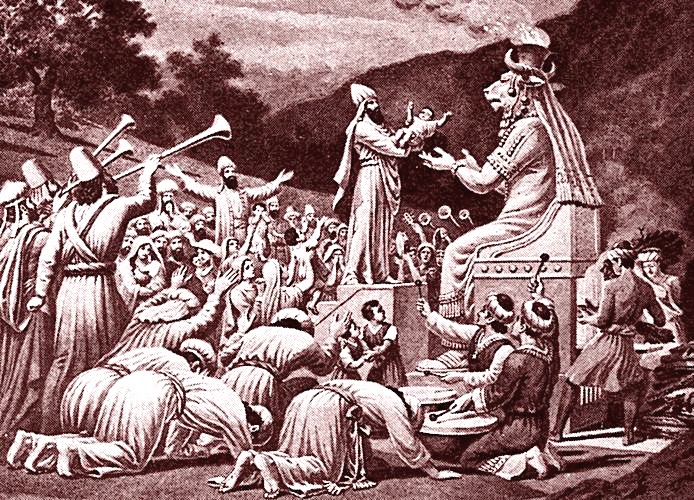

Relatively little is known about the cultural life of our Paleolithic humanoid ancestors, but what’s there suggests that ritual human sacrifice (as opposed to ritual burial, of which there is substantial evidence) was not as prevalent as it became in the later Neolithic period and beyond. This suggests that as humans’ propensity for sophisticated social interaction resulted in more complex and stratified societies – and in increased interpersonal and intergroup tension – ritual human sacrifice became more prevalent (along with warfare, a topic discussed below). From the ancient Levant to Bronze Age Northern Europe to the pre-Columbian Americas, there is ample written and archeological evidence of such rituals being commonplace.

The surrender of the Dark Ages to the Enlightenment in Europe did not bring an end to rituals of death. In his analysis of death penalty policy in the U.S., Dwight Conquergood offers insight in this direction:

The ritual frame is elastic enough to encompass conflict and chaos, yet sufficiently sturdy to channel volatile forces and disruptive tensions into an aesthetic shape, a repeatable pattern. Rituals draw their drama, dynamism, and intensity from the crises they redress (6).

So if the death penalty is, as Conquergood submits, a “performance…through which the state dramatizes its absolute power and monopoly on violence”(7), then what does that say about the state and the society that it claims to serve? The state, in this case the U.S., has evolved from its origins as a conglomeration of English settler-colonial holdings. It has arguably transformed into an oligarchic republic, the seat of a global economic and military empire. Along the way, the traditions that inform official state killings have also evolved.

For colonial Puritans, capital punishment was a process through which a wayward citizen was brought – through torture and death – into harmony with the values of the community. Thus their ritual structures were heavily laden with religious imagery, process, and theater; they were widely advertised spectacles in which perhaps thousands of citizens were invited to observe and become either active or vicarious participants (8).

By the early 19th century, though, the established and expanding independent U.S. had undergone a transformation of civic values. Communities were more diffuse, and class distinctions more sharply drawn. Condemned prisoners were now regarded as infections of the body politic, contaminants that must be neutralized and expunged. The very public theater of redemption gave way to exclusive, sanitized erasure (9).

Since experiencing a brief lull in the mid-1970s, capital punishment has made a resurgence in much of the U.S., and it has arguably distilled the values it took on in the previous century. Further, despite numerous studies demonstrating the inefficacy of the death penalty as a deterrent – and the class-based and racialized injustice inherent to its application – it remains a reliable plank of “law and order” politics (10).

Besides official state killing, there is the sordid historical record of unofficial ritual killing in the U.S.: lynching. In its heavily racialized application, lynching was a parallel and distilled tradition of its official counterpart. The people and communities of the former Confederacy sought to restore and maintain a racialized social and economic order that had been thrown into chaos and jeopardy by the devastation and upheaval of the Civil War and Emancipation.

The U.S. Constitution had been amended to offer freed blacks a measure of legal recognition, however precarious. Any fulfillment of that narrow promise was too much for the openly patriarchal, white-supremacist social order of the South, however, and the desire to maintain that social order in the face of federal legal challenges led to the construction of de facto and de jure social codes that savagely circumscribed the activity of black people. The ultimate remedy of these codes was extrajudicial lynching.

As with official state executions, lynching was a ritual for the maintenance of order, though its deployment demanded far less legal pretext – or none (11). Furthermore, unlike the sequestering of official state killing that began in the early 19th century, lynching remained a very public affair, often advertised and commercialized like its official colonial forerunner (12).

Given the dubious historical and contemporary relationship of state killing to any measurable qualities of justice, fairness, or even deterrence, it is arguable that in the U.S., at least, the death penalty serves primarily as a ritual, a performance, one designed to underscore the state’s authority to use violence in the maintenance of a preferred social order. Though it would be hazardous to attempt painting warfare – another significant office of state violence – as ritual human sacrifice in the above-established context, there are specific modes and tactics of modern warfare that hew closely to the parameters.

Conventional popular narratives of WWII assume that Allied bombings of Germany and Japan – including the nuclear detonations – generally had specific strategic goals and were necessary to defeat the Axis powers and end the slaughter. While it isn’t necessary to delve into how well those policies fit our thesis, there is enough evidence to suggest that the popular narratives are at least partly false (13)(14). Often the Allies flattened and burned population centers to demonstrate – to themselves, to the enemy, or to potential future enemies – that they could.

Such wanton killing and destruction during a time of open, formally declared warfare set a precedent for later conflicts. U.S. air power rained wholesale destruction on the Korean peninsula in the early 1950s, destroying dozens of Korean cities and killing millions of civilians. The U.S. outdid this dark achievement in Southeast Asia less than two decades later. Again, the widely accepted justification for such enthusiastic indulgences in mass slaughter during this period – the defeat of communism – fails to explain why more peaceful and cooperative strategies were left unexplored.

Within the last two decades, this predilection for targeting and eliminating civilian populations from the air has morphed into a narrower, if no more precise tactic: drone strikes. While there is little proof that the remote killings have any appreciable benefits for U.S. public safety, there is evidence suggesting they have a destabilizing effect on efforts of local authorities to achieve their own security objectives (15).

We can deduce, then, that specific strategic goals (e.g. eliminating “terrorist” threats) are irrelevant. “We cannot tolerate a safe haven for terrorists whose location is known and whose intentions are clear,” said U.S. President Barack Obama in December 2009, despite mounting evidence that all but a few drone strike victims were not “targeted” individuals, but innocent noncombatants. This leaves aside, of course, the legal and moral ramifications of the U.S. executive acting as prosecutor, judge, and executioner without any semblance of due process.

Perhaps, though, that is the point. Let us now look at one set of killings, with each incident having targeted a U.S. citizen. Alleged al Qaeda member and New Mexico-born Anwar al Awlaki, a wanted man for several years, was finally marked for death by the Obama administration, which killed him in a drone-launched missile attack in Yemen in September 2011 (16). It is debatable what strategic value or existential threat was posed by al Awlaki, who was variously described as a mastermind, a propagandist, and an inspirational figure. “The death of Awlaki is a major blow to Al Qaeda’s most active operational affiliate,” claimed President Obama (17).

It is difficult to accurately account for how many such key figures the U.S. had claimed to have neutralized since the Bush administration had begun the country’s “global war on terror” ten years earlier. Moreover, around the time of al Awlaki’s killing, the Obama administration had already seemed to relax the U.S.’s belligerent stance toward the al Qaeda brand long enough to allow affiliates of the group to do their murderous bidding in Syria (18).

The killing of al Awlaki is only the beginning of our set. Two weeks after eliminating him, U.S. forces killed his 16-year-old son, who had set out in Yemen to find his father. U.S. officials claimed this drone strike was a mistake, but never clarified that justification (19).

Five years later, Donald Trump was campaigning for president of the U.S. One of his promises was to “go after the families” of suspected terrorists (20). In late January of 2017, that promise was fulfilled when a U.S. Navy Seal team – ostensibly in Yemen to conduct a raid against al Qaeda militants, presumably none of whom were bound for imperial proxy duty in Syria – killed a number of people, most of them women and children, including 8-year-old Nawar “Nora” Anwar al-Awlaki, the aforementioned late cleric’s daughter (21).

Though the latest murder of an al Awlaki family member did not involve a drone strike, the symbolism was consistent. The U.S. executive branch, under one presidential administration after another, claimed and executed the privilege of killing anyone, including a U.S. citizen, according to its own counsel without any judicial due process. Given their dubious strategic value and high percentages of innocent deaths, such murders seem less like military tactics and more like the aforementioned lynchings: the prerogative of extrajudicial killing is assumed and then carried out.

Recall now the 1948 New Yorker readers’ collective conniption. What offended and confounded them was likely an opaque and unwelcome realization of what Shirley Jackson had so brilliantly revealed to them within familiar imagery and unadorned prose. It is also what we have revealed here: humanity has largely advanced beyond the use of stones, but we are still linked with our distant, newly civilized ancestors through our shared ritual bloodlust.

It has been many millennia since humans generally abandoned our small, familial hunter-gatherer clans for increasingly sophisticated, exploitative, and impersonal modes of coexistence. We have constantly rewritten the cultural software of our species, alienating it from the needs of our largely unchanged flesh and blood hardware. The resulting tension invariably involves violence. Some individuals and movements here and there have attempted to revert to modes of living that put us more in harmony with each other and even with the rest of nature, but the dominant tendency has been to continue formalizing and ritualizing the violence.

Finally, we must look at ritualized societal violence as just one facet of a larger tableau of destructive human behavior. Our hunger for order has metastasized far beyond our ancestors’ schemes for cooperating and coexisting beyond immediate familial groups. We are no closer than they were to mastering life, but through increasing cultural and technological sophistication our death rituals have become ever more lethal. Not satisfied with killing each other by the one or by the million, we remain immersed in catastrophically exploitative and poisonous ways of living that threaten to extinguish all life on Earth. It remains to be seen if we can finally develop the wisdom to put down the knife and step away from the altar.

In this issue

Social Contracts

WORKS CITED

1. McCarthy, Erin. “11 Facts About Shirley Jackson’s “The Lottery”.” Mental Floss. June 26, 2014. Accessed August 26, 2018. http://mentalfloss.com/article/57503/11-facts-about-shirley-jacksons-lottery.

2. Driver, Tom F. “The Act Itself: Tracing the Roots of Violence in Ritual.” Soundings: An Interdisciplinary Journal, vol. 83, no. 1, 2000, p. 113.

3. Ibid., 101.

4. Ibid., 102.

5. Bingham, Paul M. “Human Uniqueness: A General Theory.” The Quarterly Review of Biology, vol. 74, no. 2, 1999, p. 134.

6. Conquergood, Dwight. “Lethal Theatre: Performance, Punishment, and the Death Penalty.” Theatre Journal, vol. 54, no. 3, 2002, p. 342.

7. Ibid.

8. Ibid., pp. 345-47.

9. Ibid., pp. 351-52.

10. Ibid., p. 353.

11. Adams, Kenneth Alan. “Lynching, Sacrifice, and Childrearing in the New South.” Journal of Psychohistory, vol. 45, no. 4, Spring2018, pp. 246-7.

12. Ibid., p. 251.

13. McKinstry, Leo. “The Revenger’s Tragedy.” New Statesman, vol. 138, no. 4980/4981, 21 Dec. 2009, p. 52.

14. Zezima, Michael. Saving Private Power: The Hidden History of “The Good War”. Soft Skull, 2000, pp. 119-45.

15. Iqbal, Khalid. “Futility of Drone Attacks.” Defence Journal, vol. 16, no. 10, May 2013, p. 52.

16. Mazzetti, Mark, Eric Schmitt and, Robert F. Worth. “C.I.A. Strike Kills U.S.-Born Militant in A Car in Yemen.” New York Times, Late Edition (East Coast) ed., Oct 01 2011, ProQuest. Web. 6 Aug. 2018 .

17. Ibid.

18. Hughes, Michael. “U.S. Support for Al Qaeda-Linked Rebels Undermines Syrian Ceasefire.” The Huffington Post, TheHuffingtonPost.com, 22 May 2017, www.huffingtonpost.com/michael-hughes/us-support-for-al-qaeda-l_b_10089410.html.

19. al-Awlaki, Nasser. “The Drone that Killed My Grandson.” New York Times, Late Edition (East Coast) ed., Jul 18 2013, ProQuest. Web. 6 Aug. 2018 .

20. LoBianco, Tom. “Donald Trump on Terrorists: ‘Take out Their Families’ – CNNPolitics.” CNN, Cable News Network, 3 Dec. 2015, www.cnn.com/2015/12/02/politics/donald-trump-terrorists-families/index.html.

21. Szoldra, Paul. “An 8-Year-Old American Girl Was Killed during the SEAL Team 6 Raid in Yemen.” Business Insider, Business Insider, 31 Jan. 2017, www.businessinsider.com/awlaki-killed-seal-team-6-raid-yemen-2017-1